This article will explore transparent filesystem compression in Btrfs and how it can help with saving storage space. This is part of a series that takes a closer look at Btrfs, the default filesystem for Fedora Workstation, and Fedora Silverblue since Fedora Linux 33.

In case you missed it, here’s the previous article from this series: https://fedoramagazine.org/working-with-btrfs-snapshots

Introduction

Most of us have probably experienced running out of storage space already. Maybe you want to download a large file from the internet, or you need to quickly copy over some pictures from your phone, and the operation suddenly fails. While storage space is steadily becoming cheaper, an increasing number of devices are either manufactured with a fixed amount of storage or are difficult to extend by end-users.

But what can you do when storage space is scarce? Maybe you will resort to cloud storage, or you find some means of external storage to carry around with you.

In this article I’ll investigate another solution to this problem: transparent filesystem compression, a feature built into Btrfs. Ideally, this will solve your storage problems while requiring hardly any modification to your system at all! Let’s see how.

Transparent compression explained

First, let’s investigate what transparent compression means. You can compress files with compression algorithms such as gzip, xz, or bzip2. This is usually an explicit operation: You take a compression utility and let it operate on your file. While this provides space savings, depending on the file content, it has a major drawback: When you want to access the file to read or modify it, you have to decompress it first.

This is not only a tedious process, but also temporarily defeats the space savings you had achieved previously. Moreover, you end up (de)compressing parts of the file that you didn’t intend to touch in the first place. Clearly there is something better than that!

Transparent compression on the other hand takes place at the filesystem level. Here, compressed files still look like regular uncompressed files to the user. However, they are stored with compression applied on disk. This works because the filesystem selectively decompresses only the parts of a file that you access and makes sure to compress them again as it writes changes to disk.

The compression here is transparent in that it isn’t noticeable to the user, except possibly for a small increase in CPU load during file access. Hence, you can apply this to existing systems without performing hardware modifications or resorting to cloud storage.

Comparing compression algorithms

Btrfs offers multiple compression algorithms to choose from. For technical reasons it cannot use arbitrary compression programs. It currently supports:

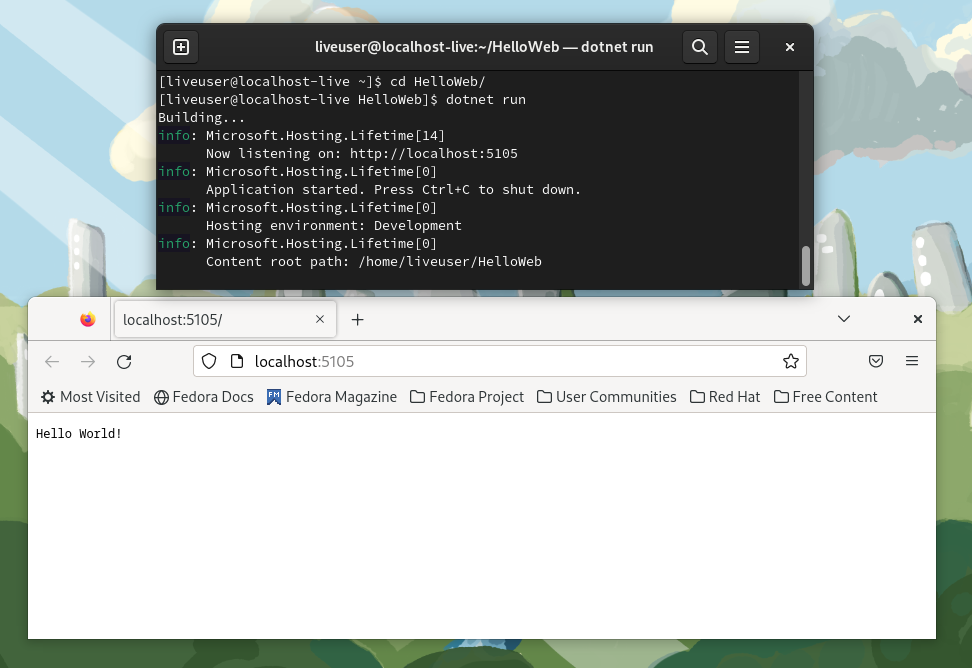

The good news is that, due to how transparent compression works, you don’t have to install these programs for Btrfs to use them. In the following paragraphs, you will see how to run a simple benchmark to compare the individual compression algorithms. In order to perform the benchmark, however, you must install the necessary executables. There’s no need to keep them installed afterwards, so you’ll use a podman container to make sure you don’t leave any traces in your system.

Because typing the same commands over and over is a tedious task, I have prepared a ready-to-run bash script that is hosted on Gitlab (https://gitlab.com/hartang/btrfs-compression-test). This will run a single compression and decompression with each of the above-mentioned algorithms at varying compression levels.

First, download the script:

$ curl -LO https://gitlab.com/hartang/btrfs-compression-test/-/raw/main/btrfs_compression_test.sh

Next, spin up a Fedora Linux container that mounts your current working directory so you can exchange files with the host and run the script in there:

$ podman run --rm -it --security-opt label=disable -v "$PWD:$PWD" \ -w "$PWD" registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora:37

Finally run the script with:

$ chmod +x ./btrfs_compression_test.sh

$ ./btrfs_compression_test.sh

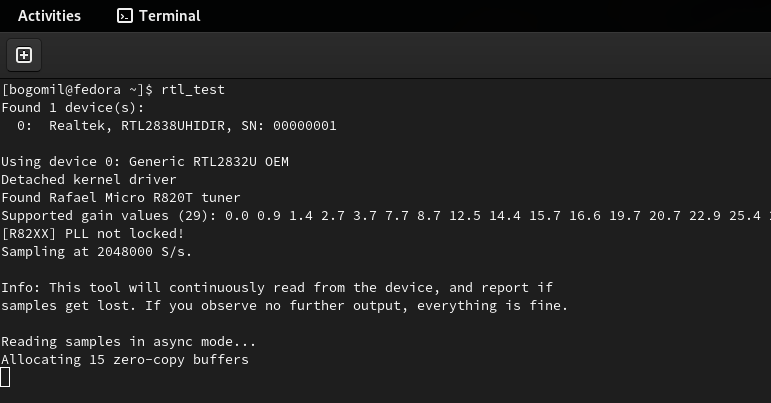

The output on my machine looks like this:

[INFO] Using file 'glibc-2.36.tar' as compression target

[INFO] Target file 'glibc-2.36.tar' not found, downloading now...

################################################################### 100.0%

[ OK ] Download successful!

[INFO] Copying 'glibc-2.36.tar' to '/tmp/tmp.vNBWYg1Vol/' for benchmark...

[INFO] Installing required utilities

[INFO] Testing compression for 'zlib' Level | Time (compress) | Compression Ratio | Time (decompress)

-------+-----------------+-------------------+------------------- 1 | 0.322 s | 18.324 % | 0.659 s 2 | 0.342 s | 17.738 % | 0.635 s 3 | 0.473 s | 17.181 % | 0.647 s 4 | 0.505 s | 16.101 % | 0.607 s 5 | 0.640 s | 15.270 % | 0.590 s 6 | 0.958 s | 14.858 % | 0.577 s 7 | 1.198 s | 14.716 % | 0.561 s 8 | 2.577 s | 14.619 % | 0.571 s 9 | 3.114 s | 14.605 % | 0.570 s [INFO] Testing compression for 'zstd' Level | Time (compress) | Compression Ratio | Time (decompress)

-------+-----------------+-------------------+------------------- 1 | 0.492 s | 14.831 % | 0.313 s 2 | 0.607 s | 14.008 % | 0.341 s 3 | 0.709 s | 13.195 % | 0.318 s 4 | 0.683 s | 13.108 % | 0.306 s 5 | 1.300 s | 11.825 % | 0.292 s 6 | 1.824 s | 11.298 % | 0.286 s 7 | 2.215 s | 11.052 % | 0.284 s 8 | 2.834 s | 10.619 % | 0.294 s 9 | 3.079 s | 10.408 % | 0.272 s 10 | 4.355 s | 10.254 % | 0.282 s 11 | 6.161 s | 10.167 % | 0.283 s 12 | 6.670 s | 10.165 % | 0.304 s 13 | 12.471 s | 10.183 % | 0.279 s 14 | 15.619 s | 10.075 % | 0.267 s 15 | 21.387 s | 9.989 % | 0.270 s [INFO] Testing compression for 'lzo' Level | Time (compress) | Compression Ratio | Time (decompress)

-------+-----------------+-------------------+------------------- 1 | 0.447 s | 25.677 % | 0.438 s 2 | 0.448 s | 25.582 % | 0.438 s 3 | 0.444 s | 25.582 % | 0.441 s 4 | 0.444 s | 25.582 % | 0.444 s 5 | 0.445 s | 25.582 % | 0.453 s 6 | 0.438 s | 25.582 % | 0.444 s 7 | 8.990 s | 18.666 % | 0.410 s 8 | 34.233 s | 18.463 % | 0.405 s 9 | 41.328 s | 18.450 % | 0.426 s [INFO] Cleaning up...

[ OK ] Benchmark complete!

It is important to note a few things before making decisions based on the numbers from the script:

- Not all files compress equally well. Modern multimedia formats such as images or movies compress their contents already and don’t compress well beyond that.

- The script performs each compression and decompression exactly once. Running it repeatedly on the same input file will generate slightly different outputs. Hence, the times should be understood as estimates, rather than an exact measurement.

Given the numbers in my output, I decided to use the zstd compression algorithm with compression level 3 on my systems. Depending on your needs, you may want to choose higher compression levels (for example, if your storage devices are comparatively slow). To get an estimate of the achievable read/write speeds, you can divide the source archives size (about 260 MB) by the (de)compression times.

The compression test works on the GNU libc 2.36 source code by default. If you want to see the results for a custom file, you can give the script a file path as the first argument. Keep in mind that the file must be accessible from inside the container.

Feel free to read the script code and modify it to your liking if you want to test a few other things or perform a more detailed benchmark!

Configuring compression in Btrfs

Transparent filesystem compression in Btrfs is configurable in a number of ways:

- As mount option when mounting the filesystem (applies to all subvolumes of the same Btrfs filesystem)

- With Btrfs file properties

- During btrfs filesystem defrag (not permanent, not shown here)

- With the chattr file attribute interface (not shown here)

I’ll only take a look at the first two of these.

Enabling compression at mount-time

There is a Btrfs mount option that enables file compression:

$ sudo mount -o compress=<ALGORITHM>:<LEVEL> ...

For example, to mount a filesystem and compress it with the zstd algorithm on level 3, you would write:

$ sudo mount -o compress=zstd:3 ...

Setting the compression level is optional. It is important to note that the compress mount option applies to the whole Btrfs filesystem and all of its subvolumes. Additionally, it is the only currently supported way of specifying the compression level to use.

In order to apply compression to the root filesystem, it must be specified in /etc/fstab. The Fedora Linux Installer, for example, enables zstd compression on level 1 by default, which looks like this in /etc/fstab:

$ cat /etc/fstab

[ ... ]

UUID=47b03671-39f1-43a7-b0a7-db733bfb47ff / btrfs subvol=root,compress=zstd:1,[ ... ] 0 0

Enabling compression per-file

Another way of specifying compressions is via Btrfs filesystem properties. To read the compression setting for any file, folder or subvolume, use the following command:

$ btrfs property get <PATH> compression

Likewise, you can configure compression like this:

$ sudo btrfs property set <PATH> compression <VALUE>

For example, to enable zlib compression for all files under /etc:

$ sudo btrfs property set /etc compression zlib

You can get a list of supported values with man btrfs-property. Keep in mind that this interface doesn’t allow specifying the compression level. In addition, if a compression property is set, it overrides other compression configured at mount time.

Compressing existing files

At this point, if you apply compression to your existing filesystem and check the space usage with df or similar commands, you will notice that nothing has changed. That is because Btrfs, by itself, doesn’t “recompress” all your existing files. Compression will only take place when writing new data to disk. There are a few ways to perform an explicit recompression:

- Wait and do nothing: As files are modified and written back to disk, Btrfs compresses the newly written file contents as configured. At some point, if we wait long enough, an increasing part of our files are rewritten and, hence, compressed.

- Move files to a different filesystem and back again: Depending on which files you want to apply compression to, this can become a rather tedious operation.

- Perform a Btrfs defragmetation

The last option is probably the most convenient, but it comes with a caveat on Btrfs filesystems that already contain snapshots: it will break shared extent between snapshots. In other words, all the shared content between two snapshots, or a snapshot and its’ parent subvolume, will be present multiple times after a defrag operation.

Hence, if you already have a lot of snapshots on your filesystem, you shouldn’t run a defragmentation on the whole filesystem. This isn’t necessary either, since with Btrfs you can defragment specific directories or even single files, if you wish to do so.

You can use the following command to perform a defragmentation:

$ sudo btrfs filesystem defragment -r /path/to/defragment

For example, you can defragment your home directory like this:

$ sudo btrfs filesystem defragment -r "$HOME"

In case of doubt it’s a good idea to start with defragmenting individual large files and continuing with increasingly large directories while monitoring free space on the file system.

Measuring filesystem compression

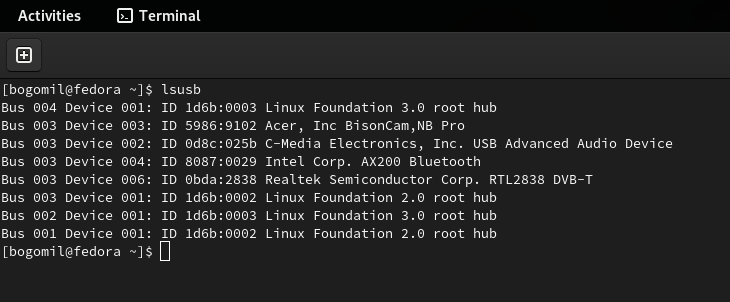

At some point, you may wonder just how much space you have saved thanks to file system compression. But how do you tell? First, to tell if a Btrfs filesystem is mounted with compression applied, you can use the following command:

$ findmnt -vno OPTIONS /path/to/mountpoint | grep compress

If you get a result, the filesystem at the given mount point is using compression! Next, the command compsize can tell you how much space your files need:

$ sudo compsize -x /path/to/examine

On my home directory, the result looks like this:

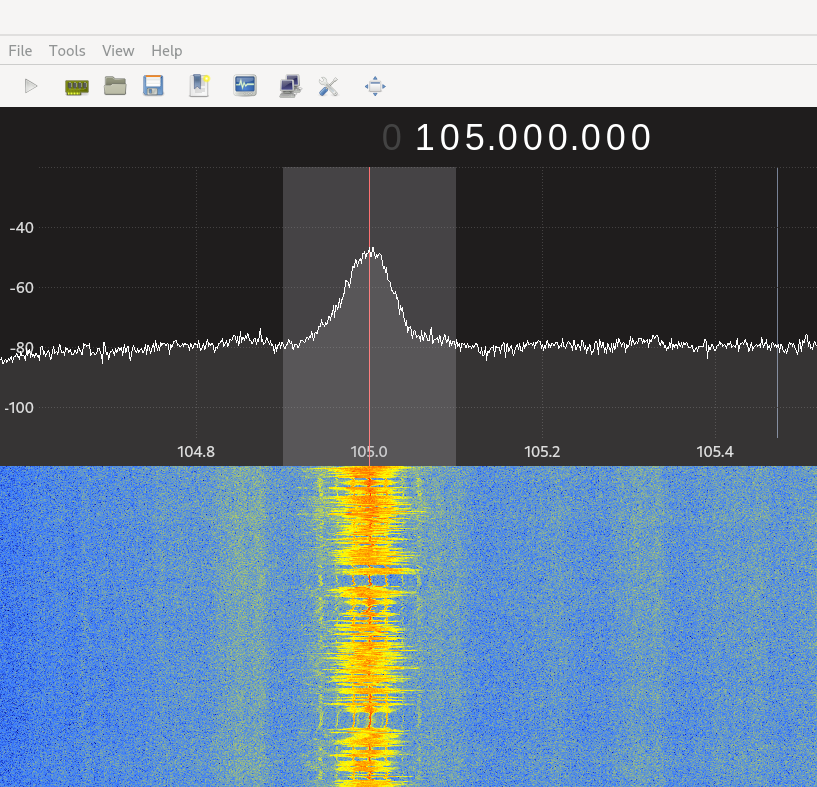

$ sudo compsize -x "$HOME"

Processed 942853 files, 550658 regular extents (799985 refs), 462779 inline.

Type Perc Disk Usage Uncompressed Referenced

TOTAL 81% 74G 91G 111G

none 100% 67G 67G 77G

zstd 28% 6.6G 23G 33G

The individual lines tell you the “Type” of compression applied to files. The “TOTAL” is the sum of all the lines below it. The columns, on the other hand, tell you how much space our files need:

- “Disk Usage” is the actual amount of storage allocated on the hard drive,

- “Uncompressed” is the amount of storage the files would need without compression applied,

- “Referenced” is the total size of all uncompressed files added up.

“Referenced” can differ from the numbers in “Uncompressed” if, for example, one has deduplicated files previously, or if there are snapshots that share extents. In the example above, you can see that 91 GB worth of uncompressed files occupy only 74 GB of storage on my disk! Depending on the type of files stored in a directory and the compression level applied, these numbers can vary significantly.

Additional notes about file compression

Btrfs uses a heuristic algorithm to detect compressed files. This is done because compressed files usually do not compress well, so there is no point in wasting CPU cycles in attempting further compression. To this end, Btrfs measures the compression ratio when compressing data before writing it to disk. If the first portions of a file compress poorly, the file is marked as incompressible and no further compression takes place.

If, for some reason, you want Btrfs to compress all data it writes, you can mount a Btrfs filesystem with the compress-force option, like this:

$ sudo mount -o compress-force=zstd:3 ...

When configured like this, Btrfs will compress all data it writes to disk with the zstd algorithm at compression level 3.

An important thing to note is that a Btrfs filesystem with a lot of data and compression enabled may take a few seconds longer to mount than without compression applied. This has technical reasons and is normal behavior which doesn’t influence filesystem operation.

Conclusion

This article detailed transparent filesystem compression in Btrfs. It is a built-in, comparatively cheap, way to get some extra storage space out of existing hardware without needing modifications.

The next articles in this series will deal with:

- Qgroups – Limiting your filesystem size

- RAID – Replace your mdadm configuration

If there are other topics related to Btrfs that you want to know more about, have a look at the Btrfs Wiki [1] and Docs [2]. Don’t forget to check out the first three articles of this series, if you haven’t already! If you feel that there is something missing from this article series, let me know in the comments below. See you in the next article!

Sources

[1]: https://btrfs.wiki.kernel.org/index.php/Main_Page

[2]: https://btrfs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Introduction.html