What’s it like to develop for visionOS? For Karim Morsy, CEO and co-founder of Algoriddim, “it was like bringing together all of the work we’ve built over many years.”

Algoriddim’s Apple Design Award-winning app djay has long pioneered new ways for music lovers and professional DJs alike to mix songs on Apple platforms; in 2020, the team even used hand pose detection features to create an early form of spatial gesture control on iPad. On Apple Vision Pro, they’ve been able to fully embrace spatial input, creating a version of djay controlled entirely by eyes and hands.

“I’ve been DJing for over twenty years, in all sorts of places and with all sorts of technology, but this frankly just blew my mind,” says Morsy. “It’s a very natural way to interact with music, and the more we can embrace input devices that allow you to free yourself from all these buttons and knobs and fiddly things — we really feel it’s liberating.”

“It’s emotional — it feels real.”

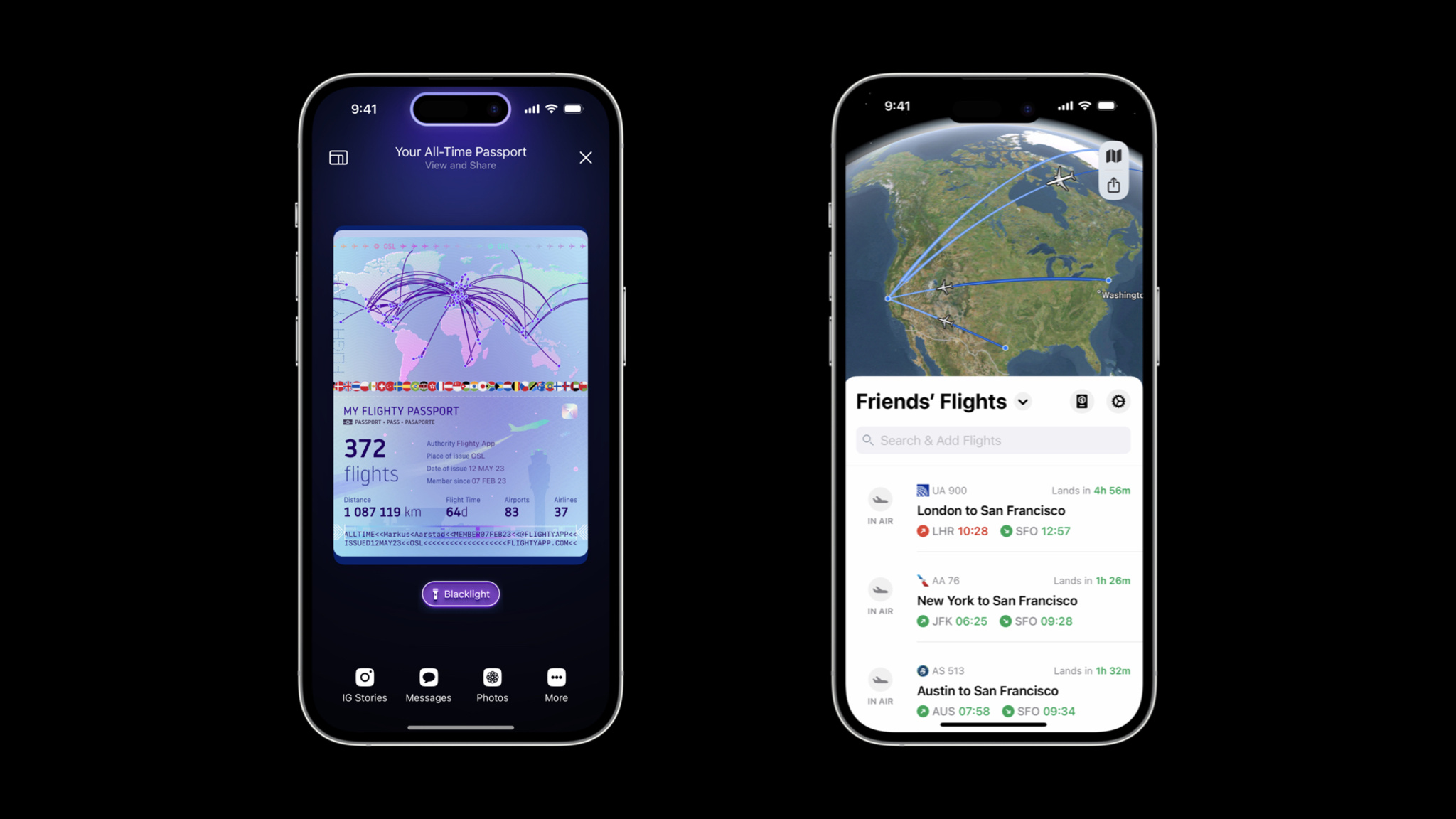

It’s a sentiment shared by Ryan McLeod, creator of Apple Design Award-winning puzzle game Blackbox. “You have a moment of realizing — it’s not even that interacting this way has become natural. There is nothing to ‘become natural’ about it. It just is!” he says. “I very vividly remember laughing at that, because I just had to stop for a moment and appreciate it — you completely forget that this [concept] is wild.”

Blackbox is famous on iOS for “breaking the fourth glass wall,” as McLeod puts it, using the sensors and inputs on iPhone in unusual ways to create dastardly challenges that ask you to do almost everything but touch the screen. Before bringing this experience to visionOS, however, McLeod had his own puzzle to solve: how to reimagine the game to take advantage of the infinite canvas offered by Vision Pro.

“You really have to go back to those first principles: What will feel native and natural on visionOS, and within a person’s world?” he says. “What will people expect — and what won’t they? How can you exist comfortably like that, and then tweak their expectations to create a puzzle, surprise, and satisfaction?”

After some early prototyping of spatial challenges, audio quickly became a core part of the Blackbox story. While McLeod and sound designer Gus Callahan had previously created sonic interfaces for the iOS app, Spatial Audio is bringing a new dimensionality to their puzzles in visionOS. “It’s a very fun, ineffable thing and completely changes the level of immersion,” he says. “Having sounds move past you is a wild effect because it evokes emotion — it feels real.”

“It will take you minutes to have your own stuff working in space.”

As someone who had exclusively developed for iOS and iPadOS for almost a decade — and had little experience with either 3D modeling or RealityKit — McLeod was initially trepidatious about trying to build an app for spatial computing. “I really hadn’t done a platform switch like that,” he says. But once he got started in Xcode, “there was a wild, powerful moment of recognizing how to set this up.”

visionOS is built to support familiar frameworks, like SwiftUI, UIKit, RealityKit, and ARKit, which helps apps like Blackbox bring over a lot of their existing codebase without having to rewrite from scratch. “What gets me excited to tell other developers is just — you can make apps really easily,” says McLeod. “It will take you minutes to have your own stuff working in space.”

Even for developers working with a more complex assortment of frameworks, like the team behind augmented reality app JigSpace, the story is a similar one. “Within three days, we had something up and running,” says CEO and co-founder Zac Duff, crediting the prowess of his team for their quick prototype.

One member of that team is JigSpace co-founder Numa Bertron, who spent a few days early in their development process getting to know SwiftUI. “He’d just be out there, learning everything he could, playing with Swift Playgrounds, and then he’d come back the next day and go: ‘Oh, boy, you won’t believe how powerful this thing is,’” Duff says.

Though new to SwiftUI, the JigSpace team is no stranger to Apple’s augmented reality framework, having used it for years in their apps to help people learn about the world using 3D objects. On Vision Pro, the team is taking advantage of ARKit features to place 3D objects into the world and build custom gestures for scaling — all while keeping the app’s main interface in a window and easily accessible.

JigSpace is also exploring how people can work together with SharePlay and Spatial Personas. “It’s a fundamental rethink of how people interact together around knowledge,” says Duff. “Now, we can just have you experience something right in front of you. And not only that — you can bring other people into that experience, and it becomes much more about having all the right people in the room with you.”

“You want to feel at home.”

Shared experiences can be great for education and collaboration, but for Xavi H. Oromí, chief engineering officer at XRHealth, it’s also about finding new and powerful ways to help people. While Oromí and his team are new to Apple platforms, they have significant expertise building fully immersive experiences: They were creating apps for VR headsets as early as 2012 in order to assist people in recognizing phobias, physical rehabilitation, mental health, and other therapy services.

Vision Pro immediately clicked for Oromí and the team, especially the fluidity of immersion that visionOS provides. “Offering some sort of gradual exposure and letting the person decide what that should look like — it’s something that’s naturally very integrated with therapy itself,” says Oromí.

With that principle as their bedrock, the team designed an experience to help people with acrophobia (fear of heights), built entirely with Apple frameworks. Despite having no prior development experience with Swift or Xcode, the team was able to build a prototype they were proud of in just a month.

In their visionOS app, a person can open a portal in their current space that gives them the feeling of being positioned at a significant height without fully immersing themselves in that app’s environment. For Oromí, this opens up new possibilities to connect with patients and help them feel grounded without overtaxing their comfort level. “You want to feel at home,” says Oromí, “The alternative before [in a completely immersive experience] was that I needed to remove the headset, and then I totally broke the immersion.”

It also has the added benefit of giving people a way to stay true to themselves. In some of their previous immersive experiences on other platforms, Oromí notes, patients’ hands and bodies were represented in the space using virtual avatars. But this had its own challenges: “We had a lot of patients saying that they felt their body was not theirs,” he says. “It’s very difficult for our society that’s so diverse to create representations of avatars that match everyone in the world… [In Vision Pro], where you can see your own body through the passthrough, we don’t need to create a representation.”

When combined with SharePlay, people can stay connected and supported with their virtual therapists while pushing their boundaries and challenging common fears. “Years from now, when we look back,” Oromí says, “we will be able to say it all started with the launch of Vision Pro — it’s where we truly enabled real virtual therapy.”

“You’re off to the races.”

When the SDK arrives later this month, developers worldwide will be able to download Xcode and start building their own apps and games for visionOS. With 46 sessions focused on Apple Vision Pro premiering at WWDC, there’s a lot of new knowledge to explore — but Duff and McLeod have a few supplemental recommendations.

“Pick up SwiftUI if you haven’t yet,” says McLeod, noting that getting to know the framework can help developers add core platform functionality to their existing app. He also suggests getting comfortable with basic modeling and Reality Composer Pro. “At some point, you’re gonna want to come off the page,” he says. But, he notes with a smile, you don’t need to become a 3D graphics expert to build for this platform. “You can get really far with a simple model and [Reality Composer Pro] shaders.”

Duff mirrors these recommendations, adding one last framework to the list: RealityKit. “If you’re transitioning from [other renderers] there are some fundamental changes you have to get to know,” he says. “But with those three things, you’re off to the races.”

Learn more about developing for visionOS and what you can do to get ready for the SDK on developer.apple.com.

Learn more about developing for visionOS

Prepare your apps for visionOS

Explore sessions about visionOS